March 2025, N°5

As spring arrives, nature itself becomes a true artisan, delighting our senses — and it's clear that its craftsmanship is nothing short of masterful. Materials and colors bloom, life awakens, revealing infinite richness in a rhythm that repeats each year, never running dry. And yet, few recognize nature as the most inventive creative director of all time. Those who do — pioneers of biomimicry and champions of biodesign — are undeniably the forerunners of a virtuous, sustainable form of craftsmanship. In fact, it may be the only truly enduring one, since its resources and techniques are endlessly renewable. Go green and discover the finest blooms of the craftsmanship of the future!

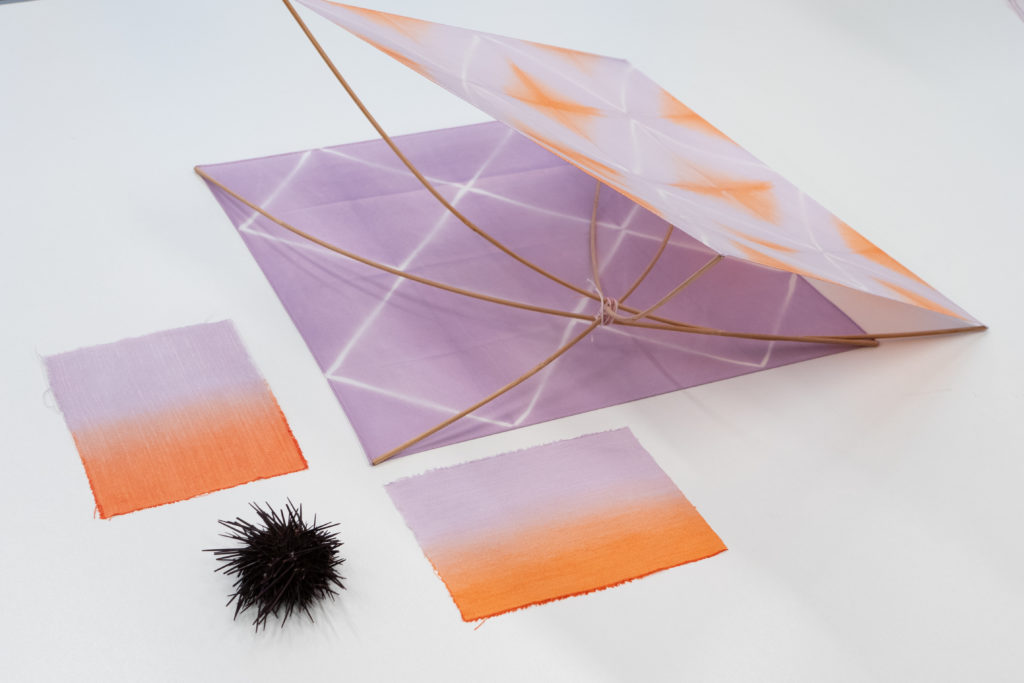

/ Textile dyeing with pigments extracted from sea urchin shells, by Atelier Sumbiosis.

Grasse wins back the good graces of the luxury world

In January, the global leader in perfumery, Givaudan, announced its plan to invest in a former industrial site in Grasse to establish its “House of Naturals” — a hub for sustainable aromatic innovation. This development echoes the recent return of luxury houses to Grasse and their crucial role in revitalizing this exceptional ecosystem. Once a major center for tanning, Grasse was transformed into an open-air perfumery to counteract the foul odors of leather processing. Over time, the city struggled against international competition, to the point where its very survival was at risk. That’s when the luxury industry stepped in. Chanel was the first, in 1987, to reconnect with the birthplace of No. 5 by initiating a partnership with a major local flower producer, the Mul family. In 2008, Dior followed suit, returning to the region near the Château de La Colle Noire — a place dear to Christian Dior — to collaborate with the Domaine de Manon, which now supplies the raw materials for its signature fragrances. Then came Louis Vuitton and Lancôme, inaugurating Les Fontaines Parfumées and the Domaine de la Rose respectively, both fully aware of the role they could play in Grasse. This renewed trust from the luxury sector in Grasse’s savoir-faire — and its support for the viability of the local supply chain and ecosystem — stems from a growing sense of responsibility among brands, which are using their influence to help preserve a truly exceptional terroir. In a mutually enriching dialogue, local producers and luxury houses are forging strong partnerships to highlight the unique, deeply rooted expertise of luxury craftsmanship and its commitment to sustainability.

THE SILKWORM WEAVES ITS WEB AT SÉRICYNE

Clara Hardy takes an interest in the silk industry, which she explores through numerous journeys. Realizing the vast scale of the silk supply chain and the repeated transformation processes involved, she begins to study shorter and more sustainable alternatives. This leads her to discover the silkworm and to found Séricyne, a company dedicated to its cultivation. The company develops the first natural, non-woven silk sheet — a patented innovation that has continued to evolve thanks to the expertise of partners specializing in its processing and refinement. The unique method involves having the silkworm produce silk directly onto the desired shapes, whether 2D or 3D, thereby giving nature a central role in every project. Séricyne has chosen to fully integrate silkworm farming and now operates the first French sericulture supply chain, which it has established in the Cévennes region. Thanks to this unique ecosystem, the company now offers a wide range of applications for this natural silk — from cosmetics and decoration to packaging. While the material is appealing for its sustainability, it’s also its velvety, felt-like touch that attracts brands and sets it apart from more conventional packaging materials. Recently, Chanel N°5 was adorned with Séricyne silk, unveiling a limited edition with haute couture flair — precious and elegant. The silkworm following in the footsteps of Coco Chanel!

ATELIER SUMBIOSIS EXPLORES NATURE’S PALETTE

A graduate of ESAD Orléans, Tony Jouaneau honed his skills in textile design under Tzuri Gueta. However, upon realizing the harmful effects of chemical finishing processes, he chose to explore sustainable alternatives and turned to biodesign through a program at ENSCI–Les Ateliers. Fascinated by the richness of nature, he founded Atelier Sumbiosis in 2018, with the aim of improving textile finishing techniques through open collaboration with living organisms. His work includes innovations such as spirulina dyeing and microbial printing on fabric. More recently, his project Slow Devored perfectly embodies his artistic vision by replacing the harshness of chemical devoré techniques with a natural process. To do this, Tony Jouaneau uses keratophagous insects, which he guides using a matrix to “devour” selected textile fibers on the chosen fabric, revealing a pattern.

Moreover, his residency at the Villa Kujoyama provided an opportunity to deepen his exploration of living matter through the ECHIRO project, in partnership with the Chemistry Laboratory of Sorbonne University. Together, they conducted research on pigment extraction from sea urchins—of which Japan is the largest consumer—and the application of this natural dye to textiles. This project, like his previous ones, reflects a commitment to bridging craftsmanship and science, and to reconciling human inventiveness with nature in order to ensure the sustainability and ongoing progress of creative practices. An approach that was justly recognized last September with the Grand Prix de la Création awarded by the City of Paris.

SENSE OF SMELL AND UNITY: THE FABRIC OF THE GRASSE ODYSSEY

A unique look into the Grasse perfume plant industry, following an interview with Armelle Janody, President of the association Fleurs d’Exception du Pays de Grasse.

At the beginning of the 20th century, with the introduction of hexane extraction, Grasse and its 5,000 perfume plant growers entered a golden age of perfumery, radiating far beyond France’s borders. But starting in the 1950s, the rise of low-cost synthetic materials posed a serious threat to the Grasse fragrance industry. Industrial clients left the region, and with growing real estate pressure, it became more profitable for farmers to sell their land than to continue cultivating it. By the end of the century, the local perfume plant sector had almost entirely disappeared. Nevertheless, a few members of the next generation set out to revive ancestral practices and unite in building a collective force. This marked the beginnings of the association Fleurs d’Exception du Pays de Grasse. After years of work to gain recognition for their expertise and the rarity of their resources, they started from scratch in 2009 by launching a small-scale farm — a “baby” operation — and began attracting their first clients back. The association makes a compelling case for the uniqueness of Grasse’s perfume plant sector. In their own words, flowers — like wine — are the expression of a specific terroir, and each slope, shaped by its own microclimate, gives rise to plants with distinct personalities: mimosa by the sea, jasmine at 300 meters altitude, narcissus in the highlands, and many more. Growing perfume flowers demands deep environmental knowledge, and this expertise is precisely what luxury brands are turning to — choosing to collaborate with local growers rather than launching their own in-house crops. Today, protected by a geographical indication and recognized as part of UNESCO’s intangible cultural heritage, the sector continues to grow in influence. Carried by 43 farmers across 24 farms — 16 of which were created entirely from scratch — and supported by its own research and development center, Grasse’s historic savoir-faire is once again in full bloom.